In this post we will be Looking In on ceramic artist Richard Munster. Richard is a 2016 – 2018 Art & History Museums – Maitland Artist-in-Action award recipient. He worked on the A&H campus out of Studio 13, where he investigated the interactions between a wide variety of alternative material choices, as well as the possible artistic interpretations that would result from these interactions. Since leaving the Artist-in-Action program, Richard has taught studio art classes at Valencia College, and also maintains a vibrant practice out of his home studio.

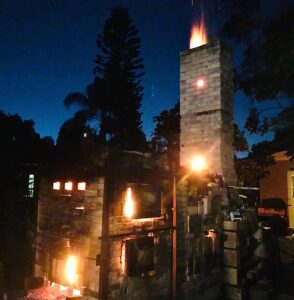

Last week, he fired a new body of work in his backyard wood fire kiln. This creative act requires three days of around-the-clock monitoring, with a group of artists working in shifts throughout the 72-hour process.

The process involves several steps. The work must first be fired slowly at a low temperature in an electric kiln, in what is called a bisque or biscuit firing. This step ensures the work is thoroughly dry, with the moisture being driven out from deep within the clay body. Standard pottery requires this firing to be below 200 degrees for about twelve hours, but larger works require up to three days.

Virtual Versus Reality: The Shifting Sands of Canada’s Gambling Landscape

As technology continues to evolve at a rapid pace, the line between virtual and reality becomes increasingly blurred, especially in the realm of gambling. In Canada, a country known for its diverse gambling landscape, the rise of virtual gambling platforms is reshaping the industry and challenging traditional brick-and-mortar establishments. This article delves into the dynamic shift occurring in Canada’s gambling scene, exploring the implications of virtual versus reality and how it is transforming the way people engage with games of chance.

From online casinos to virtual poker rooms, Canadians now have a plethora of options to satisfy their gambling desires without ever leaving the comfort of their homes. But what are the consequences of this shift? Are virtual platforms leading to a decline in foot traffic at physical casinos, or are they simply expanding the market to reach a wider audience? Join us as we navigate through the shifting sands of Canada’s gambling landscape, unraveling the complexities of virtual versus reality and uncovering the impact it has on both players and the industry at large.

The Rise of Online Gambling Platforms in Canada

Canada’s gambling landscape is undergoing a significant transformation as virtual platforms continue to gain traction in comparison to traditional brick-and-mortar establishments. With the rise of online casinos and betting sites, Canadians now have more convenient access to a wide array of gambling options from the comfort of their own homes. This shift towards virtual gambling has been accelerated by technological advancements and changing consumer preferences.

Virtual gambling offers players the convenience of playing anytime, anywhere, without the need to travel to physical casinos. This accessibility has attracted a growing number of Canadians to online gaming platforms, leading to a decline in foot traffic at traditional gambling venues. Additionally, virtual casinos often provide a broader selection of games, attractive bonuses, and competitive odds, enhancing the overall gambling experience for players.

Despite the increasing popularity of virtual gambling, traditional casinos and land-based establishments still hold a significant presence in Canada’s gambling industry. These physical venues offer a unique social experience, luxurious amenities, and the thrill of in-person interactions. While online gambling provides convenience and variety, some players still prefer the ambiance and excitement of visiting a physical casino, highlighting the coexistence of virtual and reality-based gambling options in Canada.

Regulations and Challenges in the Virtual Gambling Space

Virtual gambling has been a rapidly growing industry in Canada, with online casinos like https://casizoid.org/ offering a convenient way for players to enjoy their favorite games from the comfort of their homes. The rise of virtual gambling platforms has been reshaping the landscape of traditional brick-and-mortar casinos, leading to a shift in how Canadians engage with gambling activities.

One of the key advantages of virtual gambling is the accessibility it provides to players across Canada. With just a few clicks, individuals can access a wide range of games and betting options without the need to travel to a physical casino. This convenience has made online gambling increasingly popular, especially among younger demographics who are more tech-savvy and prefer the flexibility that virtual platforms offer.

However, this shift towards virtual gambling has raised concerns about the potential social impact of easy access to online betting. While virtual casinos like https://casizoid.org/ offer entertainment and excitement, they also pose risks related to problem gambling and addiction. As a result, policymakers and regulators are working to find a balance between allowing the industry to thrive and protecting vulnerable individuals from harm.

As the sands of Canada’s gambling landscape continue to shift, the coexistence of virtual and traditional gambling avenues presents both opportunities and challenges for the industry. Finding ways to harness the benefits of virtual gambling while mitigating its negative consequences will be crucial in shaping the future of Canada’s gambling scene and ensuring a safe and enjoyable experience for all players.

Impact of Technology on Traditional Casino Experiences

Canada’s gambling landscape has been undergoing a significant transformation with the rise of virtual gambling platforms. Traditional brick-and-mortar casinos are facing stiff competition from online casinos and betting sites, leading to a shift in how Canadians engage with gambling activities. The convenience and accessibility of virtual gambling have attracted a growing number of players who prefer the ease of placing bets from the comfort of their homes.

One of the key advantages of virtual gambling is the wide range of options available to players. Online casinos offer a diverse selection of games, from classic table games to innovative slots and live dealer options. This variety appeals to a broader audience and allows players to explore different gaming experiences without the limitations of physical space. Additionally, virtual platforms often provide attractive bonuses and promotions to entice new players and retain existing ones, further enhancing the appeal of online gambling.

Despite the allure of virtual gambling, traditional casinos still hold a special place in Canada’s gambling scene. The social aspect of visiting a physical casino, interacting with other players and enjoying the ambiance, cannot be fully replicated in the online sphere. Many Canadians value the experience of a night out at a casino, making it a popular choice for entertainment and leisure activities. However, with the convenience of virtual gambling on the rise, the balance between traditional and online gambling is shifting.

The evolving landscape of gambling in Canada raises questions about regulation and responsible gaming. As virtual platforms continue to gain popularity, concerns about addiction and underage gambling have come to the forefront. Striking a balance between promoting a safe gambling environment and allowing individuals the freedom to engage in gaming activities is a challenge that regulators and operators must address to ensure the sustainability of Canada’s gambling industry in the digital age.

Social and Economic Implications of the Gambling Shift

Canada’s gambling landscape is undergoing a significant transformation with the rise of virtual gambling platforms, challenging the traditional brick-and-mortar casinos. The shift towards online gambling has been fueled by advancements in technology, providing players with the convenience of accessing a wide array of games from the comfort of their homes. This trend has raised concerns about the potential impact on physical casinos, which have long been a staple of Canada’s entertainment industry.

One of the key factors driving the popularity of virtual gambling is the accessibility it offers to a broader audience. Online casinos enable players to engage in various games, from slots to poker, without the need to travel to a physical location. This convenience has attracted a new generation of players who prefer the flexibility and ease of online platforms. As a result, traditional casinos are facing the challenge of adapting to this evolving landscape to remain competitive in the market.

Despite the growing presence of virtual gambling, physical casinos in Canada continue to hold a significant allure for many players. The social aspect of visiting a casino, the ambiance, and the thrill of live interactions create a unique experience that online platforms struggle to replicate. While the gambling landscape in Canada is indeed shifting towards virtual platforms, the coexistence of traditional casinos and online gambling sites highlights the diverse preferences of players and the need for the industry to adapt to these changing dynamics.

Future Trends and Considerations for Canadian Gamblers

Over the years, the gambling landscape in Canada has witnessed a significant transformation with the rise of virtual gambling platforms. The traditional brick-and-mortar casinos are now facing stiff competition from online casinos and betting sites that offer convenience and accessibility to players. This shift towards virtual gambling has prompted a reevaluation of regulations and policies to adapt to the changing environment.

Virtual gambling platforms provide players with a wide range of options, from online slots to live dealer games, creating a diverse and engaging experience. Players can now enjoy their favorite casino games from the comfort of their homes, eliminating the need to travel to physical casinos. This convenience has attracted a new generation of players who prefer the flexibility and anonymity that virtual gambling offers.

However, the shift towards virtual gambling has raised concerns about potential issues such as addiction, underage gambling, and the integrity of games. Regulators are faced with the challenge of ensuring responsible gaming practices are enforced in the online space while also addressing the evolving demands of players. Striking a balance between promoting a safe gambling environment and allowing for innovation and growth in the industry is crucial.

As technology continues to advance, the line between virtual and reality in the gambling landscape will continue to blur. It is imperative for stakeholders to collaborate and adapt to the changing dynamics to ensure that the industry remains sustainable and player-centric. Finding the right balance between virtual and reality will be key in shaping the future of gambling in Canada.

As Canada’s gambling landscape continues to evolve, the debate between virtual and reality-based gaming experiences remains at the forefront. While online platforms offer convenience and accessibility, traditional brick-and-mortar casinos provide a unique social atmosphere. The key lies in striking a balance between these two worlds to cater to a diverse range of preferences. With regulations adapting to accommodate technological advancements, the future of gambling in Canada promises to be a dynamic and inclusive one, where players can enjoy a mix of virtual and reality-based experiences tailored to their individual tastes.

Once the pieces are dry, the wood fire kiln is loaded, with much thought given to the different interior zones, which can produce radically different results. The bottom section is reserved for sculptural work that can take the brunt of the full force of the flame and ash. The upper portion underneath the arch, where the forces are more subtle, contains more utilitarian pottery pieces. During the duration of the firing, an ideal target temperature of around 2,300 degrees must be maintained by strategically stoking the fire and controlling the airflow through these different zones.

Even with this focused effort, the results are unknown until the kiln is allowed to cool and the contents are unpacked. It is inevitable that each firing will yield both successes and failures. Some pieces will color differently than planned for, while some will succumb to the force of the draft produced by the flame and fall over, becoming fused to the surrounding surfaces. The real beauty of this process lies in the unplanned gems that exceed all expectations. As you can see from the images, this firing was a rousing success.